D-DAY: JUNE 6, 1944:

Preparing for the Invasion

"Everything indicates that the enemy will launch an offensive against the western front of Europe, at the latest in the spring, perhaps even earlier...."

--Adolf Hitler, Directive No. 51, November 3, 1943

From 1941 to 1944 America and its allies pursued the goal of defeating "Germany First." Their strategy rested on a key assumption, ultimately there would have to be a massive invasion of Northwest Europe aimed at the heart of the Axis empire. This would reduce German pressure on the Soviet Union by creating a true "second front" in Europe. Germany would be trapped between the Soviets in the east and the Americans and British in the west.

By 1943 success on the battlefield and production in the factories made it possible to begin formal planning for this bold operation,the largest amphibious invasion in history. The target date was spring 1944.

In Berlin, Hitler understood that an invasion would come. Fortification of the coast of Northwest Europe was already underway. In 1943 its pace accelerated and more troops were posted in the west. The Germans expected the invasion in early 1944. They knew that it would determine the war's outcome. What they did not know was precisely when and where the Allies would strike.

Operation Overlord

"This operation is not being planned with any alternatives. This operation is planned as a victory, and that's the way it's going to be. We're going down there, and we're throwing everything we have into it, and we're going to make it a success."

--General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Formal planning for the invasion of Northwest Europe began in 1943. A group led by British General Frederick Morgan searched for the best point along the coast to strike and started drawing up assault plans. In May, at an Allied conference in Washington, D.C., a target date of spring 1944 was set for the long-awaited attack.

In December 1943 a commander for the operation was selected. The choice was an American,General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Eisenhower had directed Allied invasion forces in North Africa and Italy. He took up his new post,Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force,in January 1944. Eisenhower approved of Morgan's selection of the Normandy coast in France as the invasion site, but he increased the size of the assault force. He and his staff then prepared the details of a plan to organize, transport, land, and supply the largest amphibious invasion force in history.

The operation was code-named "Overlord." The outcome of the war rested upon its success.

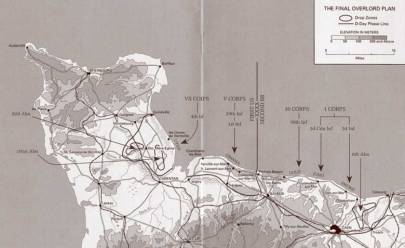

The plan for Operation Overlord entailed landing nine divisions of sea and airborne troops, over 150,000 men, along a 60-mile stretch of coast in just 24 hours.

On D-Day, three airborne divisions, one British and two American, would drop behind the landing beaches. Their job,seize beach exits, capture key transportation and communication points, and block German counterattacks.

Six divisions would assault the five landing beaches. Each beach had a code name. Utah Beach was assigned to the U.S. 4th Division. The US 29th and 1st Divisions would land at Omaha Beach. Further east, the British 50th Division would assault Gold Beach and the Canadian 3rd Division would attack at Juno Beach. The British 3rd Division would take Sword Beach.

The Commanders

"In a war such as this, when high command invariably involves a president, a prime minister, six chiefs of staff, and a horde of lesser 'planners,' there has got to be a lot of patience, no one person can be a Napoleon or a Caesar."

--General Dwight D. Eisenhower, diary entry, February 23, 1942

The seven men selected to lead Overlord, three American, four British, sat down together for the first time in January 1944. All had at least 30 years of military experience, and were regarded by their peers as exceptional in their fields. Many had served together in previous campaigns, and almost all had participated in the amphibious assaults in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations. They knew that Overlord would require Allied collaboration on an unprecedented scale.

In the months leading up to D-Day the commanders worked around the clock, planning strategic and tactical operations, conducting training exercises, and coordinating the resources and efforts of ground, air, and naval forces. There were numerous setbacks, many stemming from personality clashes and conflicting beliefs about the best course of action. When tempers flared, Eisenhower, as Supreme Commander, intervened to ease tensions among his colleagues so that Overlord would not be jeopardized. It was essential that they cooperate in what Winston Churchill called "much the greatest thing we have ever attempted."

Commander, US Ground Forces Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley

Affectionately called "the GI's General" for his unassuming manner and his concern for his soldiers, Bradley was one of the most beloved commanders in the US Army. He spent much of his early career as an instructor at his alma mater, West Point, and at the Infantry School at Fort Benning. While at Fort Benning, he played a key role in the expansion of the airborne forces. After America entered World War II, Bradley took command of the US 82nd Airborne Division. He hoped to lead the airborne troops into battle, but after only a few months he was ordered to Louisiana to rebuild a weak division of the National Guard. It wasn't until 1943 that Bradley went overseas, to North Africa. He joined his old friends, Eisenhower and General George Patton, for the Tunisian and Sicilian campaigns, before Eisenhower selected him to command the US ground forces for Overlord.

Commander, Allied Ground Forces General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery

As commander of the victorious British Army in North Africa, "Monty" enjoyed enormous popularity among both his troops and the British people. His military achievements won him the respect of his fellow soldiers, including his Desert War opponent, Erwin Rommel. But his arrogant, rigid, and abrasive manner earned him a reputation as one of the most difficult and controversial commanders of World War II. He was unreceptive to suggestions, and his cautious approach to combat led other Allied commanders to view him as weak and indecisive. And although he developed a grudging respect for Eisenhower, he made no effort to hide his contempt for the Americans, whom he regarded as second-rate soldiers. Omar Bradley, who worked closely with Monty during invasion preparations, said, "He left me with the feeling that I was a poor country cousin whom he had to tolerate."

Commander, Allied Naval Forces Fleet Admiral Sir Bertram H. Ramsay

The oldest of the Overlord commanders, Ramsay had served in the Royal Navy for over 40 years. His experience with naval operations in the English Channel during both world wars made him particularly well suited to command the Normandy invasion fleet. After World War II began, Ramsay was put in charge of laying minefields and establishing antisubmarine patrols along the Channel, the last line of defense between Britain and German-occupied Europe. He was knighted by King George VI for his success in the evacuation of nearly 340,000 Allied troops from Dunkirk in June 1940. At the time, this was the largest amphibious operation in history. Ramsay worked closely with Eisenhower and Tedder during the Allied landings in North Africa and Sicily, and Eisenhower was glad to have him appointed to Overlord. He called Ramsay "a most competent commander of courage, resourcefulness, and tremendous energy."

Commander, Allied Air Forces Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory

Leigh-Mallory achieved notoriety as a fighter commander in 1940, when he launched a controversial, though successful, offensive campaign against the Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain. Although he was a competent airman, his blatant disregard for authority, combined with a brash, argumentative style, made him extremely unpopular. As commander of the Allied air forces for Overlord, he was responsible for leading tactical air operations against both the Luftwaffe and German ground forces. But his authority was undermined by a dispute over the strategic bomber forces. Leigh-Mallory had little experience with bombing campaigns, and the British and American bomber commanders refused to take their orders from him. Air Chief Marshal Tedder assumed control over strategic operations, leaving Leigh-Mallory free to focus solely on the crucial matter of tactical fighter support for front-line ground troops.

Chief of Staff Lieutenant General Walter Bedell Smith From 1911, when he joined the Indiana National Guard as a 16-year old, Walter "Beetle" Smith advanced slowly but steadily up the army ranks. But it wasn't until the 1930s that his abilities drew significant notice. While attending the Infantry School at Fort Benning, he attracted the attention of two of his instructors, Omar Bradley and General George C. Marshall. In 1939, Marshall, at Bradley's urging, appointed Smith to the War Department. After Pearl Harbor, Smith was promoted to Secretary of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He was so highly valued by Marshall that it was only after Eisenhower pleaded to have Smith as his Chief of Staff that Marshall agreed to let him go. Smith was an excellent military manager and, as Eisenhower's right-hand man, provided administrative and moral support, helping the SHAEF staff prepare for Overlord. Eisenhower called him "a godsend."

Deputy Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder

By the time Eisenhower named Arthur Tedder as his Deputy Commander, the two men had already worked together in three invasion operations. Eisenhower described Tedder "not only as a brilliant airman but as a staunch supporter of the 'allied' principle." In North Africa, Tedder introduced an effective campaign of surgical "carpet" bombing to knock out strategic German defenses and supply lines. His air forces also carried out successful strikes against German targets in Sicily and Italy, in support of advancing ground troops. For Overlord, he would be responsible for identifying bombing targets and coordinating the activities of Allied air and ground forces. One of the most challenging aspects of his job would be working with uncooperative air commanders who refused to relinquish control of their forces. But by the spring of 1944, Tedder had managed to consolidate American and British air forces into one Allied air command.

Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force General Dwight D. Eisenhower

"When pressure mounts and strain increases everyone begins to show the weaknesses in his makeup. It is up to the Commander to conceal his: above all to conceal doubt, fear, and distrust."

Dwight Eisenhower's military career began at West Point, where he met classmate and future colleague, Omar Bradley. Although "Ike" showed promise, he was notorious for playing pranks and flaunting regulations. In a class of 164, he ranked 125th in discipline. After graduation he distinguished himself as a trainer and strategist. But he was eager to experience combat, and frustrated when he was kept stateside during World War I. His opportunity for combat command finally came during World War II, when he directed Allied forces in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. He was selected to lead Overlord not only because of his success in the Mediterranean, but because of his ability to balance the diverse personalities of the commanders involved in the operation. Even Bernard Montgomery, whose relationship with Eisenhower was often strained, said of him, "He has the power of drawing the hearts of men towards him .... He merely has to smile at you, and you trust him at once."

SHAEF: Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force

The organization formed to direct Overlord was known as Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). SHAEF was created in January 1944. It replaced an earlier Allied planning organization, COSSAC (Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander). COSSAC had mapped out the original invasion plans in 1943.

Based in Norfolk House on the outskirts of London, SHAEF was the administrative center for Overlord planning and operations. All of the commanders in the Allied Expeditionary Force reported to Eisenhower. Though the leaders of the ground forces, General Bernard Montgomery and General Omar Bradley, were not technically part of SHAEF, they took their orders directly from the Supreme Commander and worked closely with SHAEF staff.

The Invasion Site: Keeping Hitler Guessing

The main objective of Allied deception strategy was to convince the Germans that an invasion would indeed take place, but not at Normandy. The most obvious choice for an invasion site was Calais, located at the narrowest part of the English Channel, only 22 miles from Great Britain. Hitler was almost certain that the Allies would attack here. The Allies encouraged Hitler's belief by employing an ingenious ruse. Throughout southeastern England they built phony armies, complete with dummy planes, ships, tanks, and jeeps. With the help of British and American motion picture crews, they created entire army bases that would look authentic to German reconnaissance aircraft. These "bases" gave the impression of a massive Allied buildup in preparation for an invasion of France at Calais.

The ruse worked. Hitler ordered a heavy concentration of troops and artillery in the Pas-de-Calais region. In doing so, he left Normandy with fewer defenders.

Maintaining the Overlord Secret In spring 1944 SHAEF initiated the Transportation Plan, using bombers to destroy rail centers and bridges serving northwestern France. The aim was to cut supply lines to the German forces in Normandy. To avoid giving away the invasion's location, Allied aircraft also conducted bombing and reconnaissance missions near Calais. Just before the invasion commenced, additional diversionary tactics would begin. Small groups of Allied ships and planes would head towards Calais, transmitting electronic signals to simulate the approach of a large invasion fleet on German radar. Plans to isolate and confuse German forces in Normandy were aided by the French Resistance. Before D-Day, this secret army provided Allied planners with reports about German positions and activities in Normandy. Once the invasion began, they would sabotage railroad tracks and cut power and communication lines. "In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies." The success of Operation Overlord depended heavily on preventing Hitler from learning the date and location of the invasion. If the Germans were to gain advance knowledge of D-Day, the outcome could be disastrous. Additional divisions and arms could easily be deployed to Normandy in time to stop an Allied assault at the beach. The Allies needed to devise a plan that would keep the Germans in the dark about the invasion preparations. Winston Churchill was one of the chief architects of the Overlord deception plan, which was code-named "Bodyguard." Churchill's enthusiasm for including elaborate deceptions in major offensive campaigns stemmed, in large part, from the failure of earlier amphibious operations,especially those at Dieppe in World War II and at Gallipoli in World War I. In late 1943, more than six months before D-Day, the Allies,aided by the French Resistance, German double agents, and their own elaborate intelligence operations, began strategic and tactical operations to keep the Germans out of Normandy. The ENIGMA Riddle ENIGMA and D-Day Deception Plans How did ENIGMA Work? "Rupert": D-Day's Smallest Soldier "After enduring all the ordeals and training in England, we felt like we were completely ready for anything, and we were very ready to fight the Germans, and we looked forward to the day that we could actually get into the real fight." Operation Overlord required a massive buildup of men and supplies in Great Britain, the training zone and staging area for the invasion. American troops began arriving in 1942. Eventually there would be over 1.5 million American soldiers, sailors, and airmen in the United Kingdom. They joined divisions of British and Canadian troops, along with smaller contingents from France, Poland, and other nations. The presence of so many Americans caused some problems. The Yanks were paid four times what British troops received. This, and the attention the Americans paid to British women, bred resentment. "Overpaid, oversexed and over here." That was how some in Britain described the Americans. There was also tension within the American forces between black and white GIs. When they mixed in pubs there were often fights, too often culminating in a shooting. The army took to segregating the pubs. For the most part, however, the American "occupation" of Britain was carried out with remarkable success. It helped beyond measure that everyone had the same ultimate objective. The Big Buildup The invasion buildup took two years to complete. Much of the supplies and equipment, over 5 million tons, came with the Americans. By the spring of 1944 Great Britain was transformed into what General Eisenhower described as "the greatest operating military base of all time." Assault Training The amount of supplies required for the Normandy invasion was staggering. It included everything needed to outfit, feed, and arm millions of soldiers, sailors, and airmen. There were tanks, jeeps, trucks, warships, warplanes, field artillery, ammunition, rations, and medical supplies. One of the key supply problems was assembling a fleet of landing craft and ships large enough to carry ashore six divisions of troops in one day. A variety of amphibious craft were gathered,from giant LSTs to LCVPs, DUKWs (floating two-and-a-half-ton trucks) and specially equipped tanks capable of swimming to shore. The invasion buildup took two years to complete. Much of the supplies and equipment,over 5 million tons,came with the Americans. By the spring of 1944 Great Britain was transformed into what General Eisenhower described as "the greatest operating military base of all time." Assault Training Fortifying the Coast Deadly Obstacles As further protection against invasion, Rommel ordered the placement of mined beach obstacles along the French coast. Simple yet deadly, these obstacles were positioned across entire beachfronts. At high tide, many of them were virtually invisible. These obstacles created a dilemma for Allied invasion planners. If their attack came during high tide, many landing craft would hit mines. But if it took place during low tide, troops would have to cross a wider portion of beach while under enemy fire. Final Preparations

![]()

A Bodyguard of Lies

--Prime Minister Winston Churchill, 1943

The ENIGMA machine was an ingenious encrypting device employed by the Germans since the 1920s. During World War II it was used by German military and intelligence forces to transmit classified information. With over 200 trillion possible letter combinations, its code was hailed by the Germans as unbreakable. They were unaware, however, that the Allies had cracked the code with the help of Polish cryptographers who had broken some of the ENIGMA keys before the war.

By 1940 British intelligence was able to read much of the ENIGMA radio traffic. Information gathered from decrypted messages was known by the code name ULTRA. This breakthrough enabled the Allies to monitor German troop movements and gauge German reactions to Allied activity. It proved invaluable to the D-Day deception planners because it permitted them to see if the Germans accepted their misinformation as truth. Based on the German response, the Allies could alter their efforts as needed to maintain the ruse.

Despite its complex system of wires, plugs, and ciphering wheels, the ENIGMA machine was fairly simple to use. The operator just typed the letters of a message,the machine's internal mechanisms did the rest. Pressing a key sent an electrical current through the plugboard wiring and activated the wheels. The wheels rotated to produce an encrypted letter, which lit up above the keyboard. The code changed according to the wheel and plug positions. Each configuration produced a different scrambled letter. To read or write a coded message, the operator wrote down all of the letters as they lit up. Operators were given monthly charts to indicate the daily settings, because a message enciphered by an ENGIMA machine could be deciphered only by another ENIGMA machine with the same settings.

Early on D-Day morning "Ruperts" would be dropped with several real paratroopers east of the invasion zone, in Normandy and the Pas-de-Calais. The dummies were dressed in paratrooper uniforms, complete with boots and helmets. To create the illusion of a large airborne drop, the dummies were equipped with recordings of gunfire and exploding mortar rounds. The real troops would supply additional special effects, including flares, chemicals to simulate the smell of exploded shells, and amplified battle sounds. This operation, code-named "Titanic," was designed to distract and confuse German forces while the main airborne forces landed further to the west.![]()

GIs in Britain

--Sgt. Bob Slaughter, 116th Infantry Regiment, US 29th Division

The amount of supplies required for the Normandy invasion was staggering. It included everything needed to outfit, feed, and arm millions of soldiers, sailors, and airmen. There were tanks, jeeps, trucks, warships, warplanes, field artillery, ammunition, rations, and medical supplies. One of the key supply problems was assembling a fleet of landing craft and ships large enough to carry ashore six divisions of troops in one day. A variety of amphibious craft were gathered,from giant LSTs to LCVPs, DUKWs (floating two-and-a-half-ton trucks) and specially equipped tanks capable of swimming to shore.

The Allied troops preparing for D-Day pursued a routine of intense training. They spent hours at firing ranges, underwent physical conditioning, and became familiar with different landing craft. There were assault exercises at beach training sites. The men practiced exiting landing craft. They crawled under barbed wire while live fire passed over their heads. Engineers were trained to demolish beach obstacles and blow up mines. Army Rangers scaled cliffs. Paratroopers made day and night jumps and endured three-day forced marches.![]()

Fortress Europe

The Allied troops preparing for D-Day pursued a routine of intense training. They spent hours at firing ranges, underwent physical conditioning, and became familiar with different landing craft. There were assault exercises at beach training sites. The men practiced exiting landing craft. They crawled under barbed wire while live fire passed over their heads. Engineers were trained to demolish beach obstacles and blow up mines. Army Rangers scaled cliffs. Paratroopers made day and night jumps and endured three-day forced marches.

Hitler envisioned the Atlantic Wall as an unbreakable barrier, fortified with enough artillery and manpower to foil even a massive invasion attempt. Plans called for 15,000 concrete bunkers, ranging in size from small pillboxes to great fortresses. Three hundred thousand troops would man these defenses. The fortifications would be built by Organization Todt, the elite construction group of the Nazi Party. The workforce consisted of over 500,000 men, many of them prisoners or civilians from German-occupied nations, who were used as slave labor. But in January 1944, the Atlantic Wall fortifications were still incomplete, and Rommel had doubts as to whether these defenses would be sufficient.

In the final days before D-Day, the assault troops received new uniforms and equipment, as well as these special supplies issued specifically for the invasion. General Bradley severely restricted the number of items issued to soldiers, so that they would not be weighed down by extra gear when they landed in Normandy. But even lightly equipped, the average soldier would carry about 75 pounds of equipment onto the beaches.

The Invasion Begins

The Invasion Force Gathers...and Waits "All southern England was one vast military camp, crowded with soldiers awaiting final word to go.... The mighty host was tense as a coiled spring...coiled for the moment when its energy should be released and it would vault the English Channel in the greatest amphibious assault ever attempted."

-- General Dwight D. Eisenhower

In the first week of May 1944 the soldiers and sailors of the invasion force began descending on southern England. They came by boat, train, bus, or on foot from bases all over Great Britain. Almost 2 million men and nearly half a million vehicles were assembled. It was the greatest mass movement of armed forces in the history of the British and American armies. Upon their arrival in southern England, the men were confined in marshaling areas. There they began to be briefed about their mission.

General Eisenhower had set D-Day for June 5. Loading for the assault started on May 31. That night, the first part of the massive naval operation began when minesweepers moved out to start clearing channels for the armada.

Then, on June 4, with the great invasion force poised to go, trouble struck. A large storm arose in the English Channel. Eisenhower faced an agonizing decision,should he postpone the invasion?

The Decision to Go

"The waiting for history to be made was the most difficult. I spent much time in prayer. Being cooped up made it worse. Like everyone else, I was seasick and the stench of vomit permeated our craft."

--Pvt. Clair Galdonik, 359th Infantry Regiment, US 90th Division

D-Day was scheduled for June 5, 1944. But on the eve of the invasion, as the air and sea armada began to assemble, a storm arose in the English Channel. It threatened the success of the operation.

At 6:00 A.M. on June 4, Eisenhower decided to postpone the invasion for at least one day, hoping for better weather on June 6.

For the next 24 hours the men of the Allied invasion force remained sealed aboard their ships. Cramped and tense, they waited. At their bases in England, the pilots and airborne troops also marked time. Everything depended on the weather and the decision of the man in charge of Overlord, General Eisenhower.

On the Continent the Germans were confident that the storm in the Channel would postpone any planned Allied invasion. Rommel took the opportunity to return to his home in Germany to visit his family.

In the early hours of June 5, Eisenhower pondered the weather reports and the conflicting advice of his inner circle of advisers.

Around noon on June 5, Eisenhower sat at a portable table and wrote a note, which he placed inside his wallet. Pressure or fatigue led him to misdate it "July 5."

"Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that Bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone. -- July 5"

The American Airborne

The US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions landed behind Utah Beach. The mission of the "Screaming Eagles" of the US 101st Airborne was to seize the causeways that served as exits from Utah and capture or destroy bridges over the Douve River. The "All Americans" of the US 82nd Airborne were to destroy other Douve bridges and capture the town of Sainte-Mére-Église.

Things went badly for the Americans at first. Flying in darkness and under fire from German forces, many pilots dropped their men far from planned landing zones. Scattered and disorganized, the troops were forced to improvise. Though they achieved few of their objectives initially, they did confuse the Germans and disrupt their operations. By late morning, Sainte-Mére-Église was captured. The exit causeways from Utah Beach were secured by 1:00 P.M.

The British Airborne

The British 6th Airborne Division dropped behind Sword Beach. Their goals-capture two bridges over the Caen Canal and Orne River, destroy bridges over the Dives River, and neutralize the giant German artillery battery at Merville. The British operations went well. The most notable was the daring capture of the "Pegasus" bridge over the Orne Canal by gliderborne troops under the command of Major John Howard.

Special Weapons and Equipment

Because of the special nature of airborne operations, paratroopers and glidermen received items that were not used by ground troops. They carried lighter weapons, as well as other equipment that could sustain them for several days if they were unable to link up with other soldiers right away.

Zane Schlemmer US 82nd Airborne Division

Nineteen-year-old Sergeant Zane Schlemmer of the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, US 82nd Airborne Division landed in an orchard in Picauville-over a mile off-target. He fashioned this scarf from a parachute he found nearby and wore it until the war's end.

"We had jumped extremely low... and I hit in a hedgerow apple orchard, coming up with very sore bruised ribs.... I landed on the Pierre Cotelle farm, which was about a mile and half from where I should have landed.... After I landed, cleared my parachute and all, I could not join up with my people because of German fire coming from the farm house.... the firing was quite overwhelming.... I was alone. I had no idea where the hell I was other than being in France."

Eventually Schlemmer joined other paratroopers defending a hill near the Mederet River. He stayed in combat until July, when he was wounded.

The best-known piece of equipment carried by the American airborne troops was a brass "cricket"-a small toy that made a clicking sound when squeezed. Crickets were issued to the men so that they could identify one another in the dark.

One cricket was carried on D-Day by 22-year-old Private Ford McKenzie of the US 101st Airborne Division. He landed at 1:15 A.M. near the town of Sainte-Mére-Église. McKenzie wore his cricket on a string around his neck. One click on the cricket was supposed to be answered with two clicks. The troops also had a password, "flash." It was to be answered with "thunder."

"If you didn't click back, it was assumed you were the soon-to-be-dead enemy."

McKenzie later jumped into Holland and was with the US 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne

Silent Wings into Normandy

A recreation depicts the aftermath of the crash of a CG-4A Waco glider in Normandy during the early morning hours of June 6, 1944.

Many airborne troops landed in Normandy in specially designed gliders that could transport soldiers, jeeps and light artillery. American-designed Waco CG-4A gliders and British Horsa Mark II and Hamilcar gliders were towed across the English Channel by Douglas C-47 Dakota transport planes and British Albemarle, Halifax, and Stirling bombers. Over Normandy, the tow ropes were released and the gliders descended to earth.

Constructed of canvas and plywood, the Allied gliders were aptly nicknamed "flying coffins." Many broke into pieces when they crashed into hedgerows or walls. Losses among the glidermen were high. Some of the dead, including one general, were crushed by jeeps or other equipment during crash landings.

Night Drop Into Normandy

"I looked at my watch and it was 12:30. When I got into the doorway, I looked out into what looked like a solid wall of tracer bullets. I said to myself, 'Len, you're in as much trouble now as you're ever going to be in. If you get out of this, nobody can ever do anything to you that you ever have to worry about!'"

--Pvt. Leonard Griffing, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, US 101st Airborne Division

The first men to see action on D-Day were the airborne troops. Three airborne divisions,two American and one British, dropped behind the landing beaches in the hours before dawn. Over 20,000 men, the largest airborne force ever assembled,entered Normandy by glider and parachute.

The overall mission of the airborne divisions was to disrupt and confuse the Germans so as to prevent a concentrated counterattack against the seaborne troops coming in at dawn, and to protect the flanks of the invasion force at Sword and Utah beaches.

Crashing into farm fields in fragile gliders, or descending in parachutes amid antiaircraft fire, the airborne troops suffered heavy casualties. In the darkness and confusion of the pre-dawn hours, many units became scattered and disorganized. Some men who landed in flooded areas drowned. Despite these difficulties, groups of soldiers managed to form up and attack the enemy.

The Armada Strikes

"Ships and boats of every nature and size churned the rough Channel surface, seemingly in a mass so solid one could have walked from shore to shore. I specifically remember thinking that Hitler must have been mad to think that Germany could defeat a nation capable of filling the sea and sky with so much ordnance."

Lt. Charles Mohrle, P-47 pilot

Even as the armada neared the French coast, German commanders did not believe that an Allied invasion was imminent. There were no Luftwaffe or naval patrols in the area. German radar finally detected the huge fleet at about 3:00 A.M., but with Rommel at home in Germany, there was no one who could dispatch additional divisions to Normandy. The invasion force remained unchallenged until daybreak, when the German coastal batteries opened fire.

Just before the first waves of troops landed, Allied bombers and naval artillery launched a massive assault against the German positions along the coast. For 35 minutes, the landing area was pounded by over 5,000 artillery rounds and 10,000 tons of bombs.

Amid the deafening noise of the artillery barrage, LCVPs and other small craft headed for shore. They were rocked by waves that left the men soaking wet,and violently seasick. Shivering from the cold and wind, and weighed down by waterlogged gear, the soldiers prepared to land on the beach. It was almost H-Hour.

The Air Armada

On June 6 the sky over the English Channel swarmed with transport planes, gliders, bombers, and fighters. Bombers targeted German supply lines across northern France and patrolled the coast watching out for enemy forces. Over 1,000 fighters flew directly above the convoys to protect them from Luftwaffe attack. Although the presence of the fighter escorts reassured the seaborne troops, some fighters were shot at by nervous ship gunners who mistook them for German planes. As it turned out, the Luftwaffe was virtually absent on D-Day. Allied air forces controlled the skies.

The Air and Sea Armada

With more than 11,000 aircraft, 6,000 naval vessels, and 2 million soldiers, sailors, and airmen from 15 countries, the invasion force assembled for Overlord was the greatest in history. Not all of these forces were deployed on June 6, many arrived as reinforcements after the initial landings. Winston Churchill called Overlord "the most difficult and complicated operation that has ever taken place."

The Sea Armada

With nearly 5,000 vessels, the invasion fleet deployed on June 6 was an inspiring and impressive sight. An American bomber pilot, looking down at the fleet, observed, "We could see the battleships firing at the coast. And literally you could have walked, if you took big steps, from one side of the Channel to the other. There were that many ships out there." But the sight of the approaching armada terrified the Germans stationed on the coast. One German officer marveled, "It's impossible ... there can't be that many ships in the world."

Caption for map showing sea routes: Seaborne Troop Routes On the morning of June 5, the ships and boats assigned to the assault forces embarked from various ports along the coast of Great Britain. They sailed for the assembly area, which was nicknamed "Piccadilly Circus." After the minesweepers swept sea lanes clear of German minefields, the assault convoys moved into transport areas located 11 miles off their assigned beaches. Here the troops transferred to LCVPs and other landing craft that would bring them to shore.

D-Day Naval Vessels

Over 50 types of naval craft participated in the initial assault operations. The sea armada included warships, escort ships, patrol and torpedo boats, and landing craft of various sizes and shapes. Most were American and British, but the Canadian, French, Polish, Norwegian, Dutch, and Greek navies also contributed ships and personnel. All vessels crossed the Channel under their own power except for the smallest landing craft, which were transported on the larger boats.

The Landing Beaches

"It was a weird feeling, to hear those heavy shells go overhead. Some of the guys were seasick. Others, like myself, just stood there, thinking and shivering. There was a fine rain and a spray, and the boat was beginning to ship water. Still, there was no return fire from the beach, which gave us hope that the navy and the air force had done a good job. This hope died 400 yards from shore. The Germans began firing mortars and artillery."

--Sgt. Harry Bare, 116th Infantry Regiment, US 29th Division

As dawn came to the coast, Allied troops approached the landing beaches. The first waves included 30-man assault teams and amphibious duplex (DD) tanks that plowed through the water under their own power. There were also army combat engineers and navy demolition teams. Their job was to clear beach obstacles and mark safe pathways for the later waves.

Aboard the landing craft the men were pitched about. Many were seasick. Tension, fear, and anticipation were the dominant emotions. Behind them the naval bombardment continued, while overhead, bombers went on with their work. The noise was tremendous. It left an unforgettable impression on every man who experienced it.

Closer to shore, boats began to hit mines. The explosions lifted some entirely out of the water. As the first waves neared land, shelling of the beaches ceased. It would not resume until the men were ashore and could radio back targets. Sometime around 6:30 A.M., the first landing craft hit the beach. D-Day had arrived on the beaches of Normandy.

Utah

"There was this barbed wire area and a wounded officer who had stepped on an antipersonnel mine calling for help. I decided that I should go. I walked in toward him, putting each foot down carefully and picked him up and carried him back. That was my baptism. It was the sort of behavior I expected of myself."

--Lt. Elliot Richardson, medical detachment

Because of differences in tides, the American beaches, Utah and Omaha, were assaulted first.

Utah Beach was assigned to the US 4th Division. H-Hour, when the attack would begin, was 6:30 A.M. The initial assault force included rifle companies, combat engineers, and naval demolition teams. There were also 32 amphibious tanks. Four tanks sank offshore. But 28 made it safely to the beach.

As the first wave neared the coast, strong currents swept the boats south. They beached 2,000 yards from the planned landing zone.

Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr., son of America's 26th president and, at age 56, the oldest member of the assault forces, was with the first wave. He and other officers assessed the situation, then quickly made a decision, they changed the landing site to their location.

This action saved many lives. The new landing zone was less defended than where the troops were supposed to land. By 9:30 A.M., three beach exits were secure. Before noon, the US 4th Division made contact with airborne forces behind the beach. As night fell, they were four miles inland. All this was achieved with remarkably few casualties, approximately 200 dead and wounded.

"When we first came in there was nothing there but men running, turning, and dodging. All of a sudden it was like a beehive. Boats were able to come through the obstacles. Bulldozers were pushing sand up against the seawall and half-tracks and tanks were able to go into the interior. It looked like an anthill."

--Seabee Orval Wakefield, underwater demolition team

"I jumped out in waist-deep water. We had 200 feet to go to shore and you couldn't run, you could just kind of push forward.... then we had 200 yards of open beach to cross, through the obstacles. But fortunately, most of the Germans were... all shook up from the bombing and the shelling and the rockets and most of them just wanted to surrender."

--Sgt. Malvin Pike, 8th Infantry Regiment, US 4th Division

"I saw what looked like a low wall ahead, so I crawled for it.... To my right was a dead GI. To my left about 40 yards away were some GIs in the process of regrouping. As I watched, they went over the wall, so I decided to flip over it also. When I looked ahead, there was no more sand; it was a swamp of shallow water. But I was on my way now."

Omaha Beach: Visitors to Hell

"As our boat touched sand and the ramp went down, I became a visitor to hell. I shut everything out and concentrated on following the men in front of me down the ramp and into the water."

--Pfc. Harry Parley, 116th Infantry Regiment, US 29th Division

If the Germans were going to stop the invasion anywhere, it would be at Omaha Beach. A wide, sandy beach, it was an obvious landing site. At each end of the beach there were cliffs running nearly perpendicular to the water. Behind the beach was a well-fortified bluff that rose 100 to 170 feet. The Germans had every inch of Omaha pre-sited with deadly crossfire.

The US 1st and 29th Divisions and men of the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions had to cross Omaha Beach and seize several "draws," ravines set into the bluff that offered passage inland.

Trouble began offshore. Thirty-two out of the 36 amphibious tanks accompanying the assault troops sank. Smoke and dust from the naval bombardment and strong currents pulled many boats off target. The first waves were nearly wiped out before the men got across the beach. Some died before they exited their boats. Survivors crouched behind beach obstacles or crawled up the beach as the tide rose behind them. Many took shelter behind a sea wall.

Follow-up waves piled up behind the first, creating a traffic jam of men and vehicles, easy targets for the Germans. Omaha Beach became a killing field.

"The first sight I got of the beach, I was looking through a sort of slit up there, and it looked like a pall of dust or smoke hanging over the beach."

--Lt. Ray Nance, Executive Officer, 116th Infantry Regiment, US 29th Division

"...we were hearing noises on the side of the landing craft like someone throwing gravel against it. The German machine gunners had picked us up. Everybody yelled, 'Stay down!'... I noticed the lieutenant's face was a very gray color and the rest of the men had a look of fear on their faces. All of a sudden the lieutenant yelled to the coxswain, 'Let her down!' The ramp dropped...."

--Pvt. H. W. Schroeder, 16th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 1st Division

"... the craft gave a sudden lurch as it hit an obstacle and in an instant an explosion erupted.... Before I knew it I was in the water.... Only six out of 30 in my craft escaped unharmed. Looking around, all I could see was a scene of havoc and destruction. Abandoned vehicles and tanks, equipment strung all over the beach, medics attending the wounded, chaplains seeking the dead."

--Pvt. Albert Mominee, 16th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 1st Division

These chaotic photographs of Omaha Beach were shot by famed war photographer Robert Capa. Capa accompanied men from Company E of the 16th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 1st Division in the second assault wave. He landed at the Easy Red sector. His dramatic but chilling photographs capture soldiers struggling through the surf and crouching for cover behind beach obstacles and tanks. Some men have fallen, whether from wounds or by mishap we do not know.

Capa shot 106 photographs of the beach. Then, his nerve broken by the carnage around him, he climbed aboard a landing craft headed back to sea. Capa's three rolls of film were rushed to London, where a darkroom technician developing them dried the negatives too quickly. He inadvertently destroyed all but 10 shots.

These blurred and grainy images are the closest we will ever come to the experience of being on Omaha Beach on the morning of June 6, 1944.

Omaha Beach: The Struggle to Survive

"There were... men there, some dead, some wounded. There was wreckage. There was complete confusion. I didn't know what to do. I picked up a rifle from a dead man. As luck would have it, it had a grenade launcher on it. So I fired my six grenades over the cliff. I don't know where they went but I do know that they went up on enemy territory."

--Pvt. Kenneth Romanski, 16th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 1st Division

The men who landed at Omaha Beach on the morning of June 6 had to overcome tremendous odds simply to survive. General Omar Bradley, who commanded American ground forces on D-Day, later wrote, "Every man who set foot on Omaha Beach that day was a hero."

The dazed and wounded men who survived the initial assault were, at first, disorganized and unable to move off the beach. Shock and fear kept them from moving forward. It took the initiative of junior and noncommissioned officers, along with ordinary privates, to turn the tide at "Bloody Omaha." These anonymous leaders had watched comrades die in the surf and on the beach. Now they led others in the only direction they could go, inland.

"Face downward, as far as eyes could see in either direction, were the huddled bodies of men living, wounded, and dead, as tightly packed together as a layer of cigars in a box.... Everywhere, the frantic cry, 'Medics, hey, Medics' could be heard above the horrible din."

--Maj. Charles Tegtmeyer, Surgeon, 16th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 1st Division

"...I crawled in over wounded and dead but I couldn't tell who was who and we had orders not to stop for anyone on the edge of the beach, to keep going or we would be hit ourselves....I ran into a bunch of my buddies from the company. Most of them didn't even have a rifle. Some bummed cigarettes off of me.... The Germans could have swept us away with brooms if they knew how few we were and what condition we were in."

--Pvt. Charles Thomas, 16th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 1st Division

This remarkable series of photographs depicts men of the 16th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. 1st Division as they huddled under chalk cliffs at the edge of the Omaha Beach near Colleville-sur-Mer.

It is morning on D-Day and the men, some of them wounded, are regrouping before moving inland. The fear, exhaustion, and determination on the faces of these soldiers hint at the terrors they have already endured.

Omaha Beach: Turning the Tide

"When you talk about combat leadership under fire on the beach at Normandy, I don't see how the credit can go to anyone other than the company-grade officers and senior NCOs who led the way. It is good to be reminded that there are such men, that there always have been, and always will be. We sometimes forget, I think, that you can manufacture weapons, and you can purchase ammunition, but you can't buy valor and you can't pull heroes off an assembly line."

--Sgt. John Ellery, 16th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 1st Division

Two things happened to reverse the disaster at Omaha Beach. First, navy destroyers moved in close to the shoreline, some of them touching sand, to deliver point-blank fire at German-fortified positions. Second, individual officers took the lead and got the troops organized to move across the beach and up the bluff. They did so by setting a personal example and by pointing out the obvious,to stay on the beach meant certain death and retreat was impossible.

The men, organized into groups that mixed companies and regiments, moved up the bluff by advancing between the well- fortified draws, not up them. In innumerable firefights, they cleared out the trenches, then attacked the fortified artillery emplacements from the rear. By afternoon the draws were still closed, but the Americans had taken Colleville-sur-Mer, Vierville-sur-Mer, and Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer. Though far short of their planned goals, they had pushed over a mile inland. They had prevailed in what was by far the best defended of the D-Day beaches. But the cost had been steep. Two thousand two hundred men, one of every 19 who landed at Omaha Beach on D-Day, were dead or wounded.

The Rangers of Pointe du Hoc

"Located Pointe du Hoc, Mission accomplished, Need ammunition and reinforcements, Many casualties."

--Lt. Col. James Rudder, 2nd Ranger Battalion, D-Day message

Between Utah and Omaha Beaches stands a large promontory called Pointe du Hoc. Allied planners learned the Germans had placed a battery of 155 mm howitzers here. With a firing range of 14 miles, these guns threatened the assault forces on both American beaches.

Allied planners gave two battalions of U.S. Army Rangers the job of neutralizing the German guns. These elite troops were trained to make an amphibious landing on the beach in front of Pointe du Hoc, scale its 100-foot cliffs, and destroy the German battery.

On D-Day the Rangers, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Rudder, used rocket-propelled grappling hooks attached to ropes and ladders to climb the cliffs. As they worked their way up, the Germans dropped grenades on them and cut some of their ropes. Still, within five minutes, the Rangers made it to the top and drove off the defenders.

They then made a startling discovery, the German guns were missing. Sergeant Len Lomell and two other Rangers scouted inland. A short distance away they found the guns. They quickly destroyed them.

By 9:00 A.M. the Rangers had accomplished their mission. But for the next two days they faced intense German counterattacks. The 2nd Ranger Battalion took over 50 percent casualties.

"We fired our rockets with the grappling hooks two at a time. Some ropes didn't make it to the top of the cliff.... the enemy cut some, but we did have enough of them... to get the job done. I was the last one in from my boat, and when I finally got to the base, there was a rope right in front of me, so I started to go up.... The enemy was shooting at us, and throwing grenades by the bushel basketful."

--Cpt. James Eikner, 2nd Ranger Battalion.

Sword

"...stamped in my memory is the sight of Shimi Lovat's tall, immaculate figure striding through the water, rifle in hand, and his men moving with him up the beach to the skirl of Bill Millin's bagpipes."

--Commander Rupert Curtis, 200th LCI Flotilla

At the easternmost end of the invasion front lay Sword Beach. The attack on Sword was spear-headed by the British 3rd Division. The assault force included commandos of the 1st Special Service Brigade. This brigade included British, French, Polish, and German Jewish troops. They were led by Brigadier Lord Simon "Shimi" Lovat.

The landings at Sword Beach went smoothly. Most of the tanks and armored vehicles made it safely to shore and the invaders quickly broke through the German coastal defenses and moved inland. The commandos, some riding collapsible bicycles, raced to link up with the paratroopers and gliderborne troops of the British 6th Airborne Division.

However, as the invaders advanced towards the city of Caen, they collided with tanks from the German 21st Panzer Division. The Germans tried to push the invasion force back into the sea. Though they withstood a fierce afternoon counterattack by the panzers, the British could not break through the German lines and seize Caen. The city, an important D-Day objective, would remain in German hands for weeks. (with 17.11.14)

"The beach was now covered with men. They were lying down in batches.... There were a good many casualties, the worst of all being the poor chaps who had been hit in the water and were trying to drag themselves in faster than the tide was rising."

--Cpt. Kenneth Wright, Intelligence Officer, 4th Commandos, 1st Special Service Brigade

"Nobody dashed ashore. We staggered. With one hand I carried my gun, finger on the trigger, with the other I held onto the rope-rail down the ramp, and with the third hand I carried my bicycle."

--Cpl. Peter Masters, 6th Commandos, 1st Special Service Brigade

Gold and Juno

"It was absolutely like clockwork. We knew it would be. We had every confidence. We had rehearsed it so often, we knew our equipment, we knew it worked, we knew given reasonable conditions we could get off the craft."

-- Lt. Pat Blamey, British 50th Division, Gold Beach

East of the American beaches lay Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches,assigned to three divisions from Great Britain and Canada. Differences in tides meant that the British and Canadians landed about one hour after the Americans.

Gold Beach was allotted to the British 50th Division. The British were aided by a collection of unusual vehicles designed by Major General Sir Percy Hobart. Dubbed "Hobart's Funnies," they included a tank outfitted with flame- throwers and one with a set of chains that flailed in front of it to destroy mines. The British ran into stiff German resistance at a fortified seaside village named La Rivire, but by noon the entire 50th Division was ashore. By day's end the British advanced to within two miles of Bayeux. Casualties numbered just 400.

Losses were far greater at Juno Beach, located adjacent to Gold. Juno was assaulted by the Canadian 3rd Division. Rough seas and strong tides hampered the Canadians. Nearly one-third of their landing craft was damaged or destroyed by mines and beach obstacles. The first wave of infantry took terrible losses. Casualties at Juno would total 1,200 by the end of the day. Still, by midmorning the Canadians were able to begin moving inland to link up with British forces from Gold.

"My buddy, Kelly McTier, who was on my right, was shot in the face and neck. We were told not to stop and help any of our buddies as we too might be hit, and we were to carry on as best we could to get across the beach."

--Wilfred Bennett, Royal Winnipeg Rifles, Canadian 3rd Division, Juno Beach

"As we approached the beach at Bernires, tracer bullets could be seen heading in our general direction from a supposedly empty pillbox about 200 yards on our right. We landed in three feet of water, and I recall thinking that no matter what lay ahead, it was a great relief to be on dry land again."

--Lt. Peter Rea, Queen's Own Rifles, Canadian 3rd Division, Juno Beach

"It looked like a Hollywood scene in a way, but it wasn't. People were being killed all around us."

--Pfc. Walter Rosenblum

"There was a landing craft breached, either due to fire or to being grounded, and quite a few men on it were not getting off and the craft was going down. We swam out and took a few...back to shore. Somebody else got a long rope which we swam out with, tied onto the landing craft, and had them hold onto...and walk themselves in.... At that time I had no idea there was a photographer in the vicinity."

--2nd Lt. Walter Sidlowski, 348th Combat Battalion, 5th Engineer Special Brigade

"I saw this magnificent man swim out and bring some people off the sinking ship and bring them back in to shore and to me he was the picture of heroic beauty."

--Pfc. Walter Rosenblum, describing the rescue efforts of Lieutenant Walter Sidlowski

D-Day: the Aftermath

"The first night in France I spent in a ditch beside a hedgerow wrapped in a damp shelter-half and thoroughly exhausted. But I felt elated. It had been the greatest experience of my life. I was 10 feet tall. No matter what happened, I had made it off the beach and reached the high ground. I was king of the hill, at least in my own mind, for a moment."

-- Sgt. John Ellery, 16th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 1st Division

As full darkness came to the Normandy coast, at about 10:00 P.M., unloading at the beaches ceased. In a single day over 150,000 American, British, Canadian, and French troops had entered France by air and sea, at a cost of nearly 5,000 casualties. From the American airborne on the far right to the British airborne on the far left, the invasion front stretched over 50 miles.

The Germans had taken years to build the Atlantic Wall. At Utah Beach, it had held up the U.S. 4th Division for less than one hour. At Omaha Beach, it had held up the U.S. 29th and 1st Divisions for less than one day. At Gold Beach, Juno Beach, and Sword Beach, it had held up the British 50th, the Canadian 3rd, and the British 3rd Divisions for about an hour. Fortress Europe had been breached. The largest amphibious operation in history was a success.

"He suddenly raised his body and let out an awful yell. He had realized that his right leg was missing. I pushed him back down and I remember him saying, 'What am I gonna do? My leg, I'm a farmer.'"

--Pharmacist's Mate Frank Feduik, administering morphine to a GI on the deck of an LST

"I noticed that nothing moved on the beach except one bulldozer. The beach was covered with debris, sunken craft, and wrecked vehicles. We saw many bodies in the water....We jumped into chest-high water and waded ashore. Then we saw that the beach was literally covered with the bodies of American soldiers wearing the blue and gray patches of the 29th Infantry Division."

--Lt. Horace Henderson, 6th Engineer Special Brigade, describing Omaha Beach on June 7.

The Breakout of Normandy

"Fighting is from field to field and from hedgerow to hedgerow. Frequently you don't know whether the field next to yours is occupied by friend or foe.... You rarely speak of advancing a mile in a single day; you say, instead, 'We advanced 11 fields.'"

-- Staff Sgt. Bill Davidson, combat correspondent, Yank, U.S. Army

At daybreak on June 7 the Allies began moving inland to expand their toehold in Normandy. A key objective was to capture a port to speed the buildup of men and supplies. American forces drove west to cut off the Cotentin Peninsula and seize the port city of Cherbourg.

As they moved inland, the Americans entered an environment perfectly designed for their opponents. Western Normandy was covered with a maze of hedgerows, thick banks of earth eight to 10 feet high covered with overgrowth and trees. For centuries, local farmers had used hedgerows to mark the boundaries of fields. Now they formed excellent defensive terrain. The Germans had pre-sited mortars and artillery on gaps in the hedgerows. Behind them, they dug rifle pits and tunneled openings for machine guns. The hedgerows had to be taken one by one. The cost in time and casualties proved high.

Meanwhile, to the east, the Canadians and British were bogged down in their effort to break out of the beachhead and seize the city of Caen. The battle for Normandy developed into a long and deadly struggle.

Victory in Europe

"'This is D-Day,' the BBC announced at 12 o'clock. 'This is the day.' The invasion has begun!... Is this really the beginning of the long-awaited liberation? The liberation we've all talked so much about, which still seems too good, too much of a fairy tale ever to come true?... the best part of the invasion is that I have the feeling that friends are on the way. Those terrible Germans have oppressed and threatened us for so long that the thought of friends and salvation means everything to us!"

-- Anne Frank, diary entry, June 6, 1944

News of D-Day electrified the world. At last the Allies had a "second front" in Europe. The Germans now faced the Soviets in the east and the Americans, British, and Canadians in the west. Hitler also had to contend with Allied armies in Italy and the ongoing Allied bombing offensive against Germany. Victory in Europe seemed within reach.

In reality, nearly a year of hard fighting lay ahead.

During June 1944 the Allies made important advances. On June 22 the Soviets unleashed a major offensive on the eastern front. In six weeks of intense battle they drove the Germans lines back into Poland.

Meanwhile, in Normandy, on the morning of June 7, the invasion entered a new phase. The Allies and the Germans rushed to move reinforcements into place. Allied air power made this difficult for the Germans, who were also hampered by Hitler's continuing belief that the Normandy invasion was just a diversion. In contrast, the Allies had men, tanks, guns, and supplies offshore and in England ready for unloading. They were poised to win the battle of the buildup.

TAKE ACTION:

EDUCATION PROJECTS:

Student Travel – WWII Educational Tours

High school and college students, learn the leadership principles that helped win WWII on a trip to France or during a weeklong residential program in New Orleans. College credit is available, and space is limited.

See You Next Year! HS Yearbooks from WWII

Collected from across the United States, the words and pictures of these yearbooks present a new opportunity to experience the many challenges, setbacks and triumphs of the war through the eyes of America’s youth.

The Victory Gardens of WWII

Visit the Classroom Victory Garden Project website to learn about food production during WWII, find lesson plans and activities for elementary students, get tips for starting your own garden and try out simple Victory Garden recipes!

The Science and Technology of WWII

Visit our new interactive website to learn about wartime technical and scientific advances that forever changed our world. Incorporates STEM principles to use in the classroom.

Kids Corner: Fun and Games!

Make your own propaganda posters, test your memory, solve puzzles and more! Learn about World War II and have fun at the same time.