LESSON PLAN:

In His Own Words: Analyzing a D-Day Diary

The most famous diary to come out of World War II was written by Anne Frank, a young Jewish girl who hid with her family from the Nazis in an Amsterdam attic. But Anne Frank was not the only person during that great global conflict to keep a daily record of her thoughts and actions. Many men and women, experiencing the thrills, horrors, uncertainties, novelties and boredom of a soldier or civilian’s life kept private diaries of their wartime experiences.

Objective:

Students will read portions of Sidney Montz’s D-Day diary, gaining knowledge of D-Day, and analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of using a diary as a primary source for historical research.

Grade Level: 7-12

Standards:

History Thinking Standard 2— student comprehends a variety of historical sources and can reconstruct the literal meaning of a historical passage and identify its central message.

Content Era 8 (1929-1945), Standard 3B—the student understands World War II and how the Allies prevailed.

Time Requirement: One to two class periods

Download a printable pdf version of this lesson plan

Directions:

1. Read aloud or have students read to themselves the introductory information about using a diary as a primary historical source and then have them do the same with the background information about Sidney Montz’s diary and D-Day.

2. Have students read the edited selections from Montz’s diary. You may provide them with the vocabulary list or have them underline any words they do not understand and have them attempt to define the unknown words using a variety of reference sources.

3. Students should complete the activity sheet. Review answers as a class.

4. Have a class discussion about the strengths and weaknesses of a diary as a primary source (discussion questions are included).

5. Share with the class the information about Montz’s final year of war.

6. Choose one or more of the suggested classroom activities for them to complete on their own in the class or as homework.

Assessment:

Components for assessment include the worksheet, the class discussion, and any extension activity assigned.

Enrichment:

Have students keep a journal about their lives for a week, writing for five minutes in class each day. Instruct them to include descriptive details of their actions and thoughts. Students can volunteer to share their entries with the class, but may keep them private, if they wish. At the end of the week, ask students again the discussion questions for using a diary as a primary source.

Using a Diary as a Primary Source

For the historical researcher, a diary can be a wonderful source for personal insights and first person accounts of people and events—two types of information often missing from more formal writings or official documents. A diary is generally written very close in time to when events occur, so personal memories may be more reliable than they would be in a memoir or oral interview created years later. Furthermore, a person often writes a diary only for himself or herself—with no thought of it becoming a public record. By not writing for an audience, the diarist’s entries may be more honest and forthright.

But is a diary a completely reliable primary source? Even if a diary entry is written close to the time of an event, the diarist can still be mistaken about his or her facts and recollections. The diarist has a very limited viewpoint and may witness things or interpret events from a narrow perspective. He or she may unintentionally alter the facts to fit some emotional need. Or he or she may purposely misrepresent the facts for a variety of reasons. The value of a diary, like any other piece of primary research, must be evaluated and used cautiously by the careful researcher.

The Diary of Sidney J. Montz

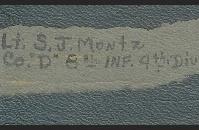

Photo on Loan from Eisenhower Center, University of New Orleans

Sidney J. Montz was a lieutenant in Co. D, 8th Regiment, of the 4th Infantry Division, US Army. The 4th Division was one of five U.S. divisions that assaulted Utah and Omaha Beaches on June 6, 1944—D-Day. Sidney was born in Louisiana in 1914, served as an ROTC corporal at Louisiana State University, and became a lieutenant in the United States Army when he enlisted in August 1942. On D-Day he was 29 years old. It would be his first combat.

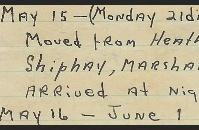

Sidney kept a diary on a small pad of paper from May 15, 1944 and July 31, 1944. He may have kept diaries during other periods of the war, but this small pad was the only diary found in a trunk of personal possessions donated by his son to The National WWII Museum in New Orleans.

This diary is one story of 175,000 that could be told about D-Day. But from a total of 59 short entries (only 25 are shown here), an alert researcher can discover a lot of information about D-Day, a soldier’s life in the European Theater during WWII, and Montz’s feelings about this turning point in the war and in his life.

Diary Entries

Directions: Read the following edited diary entries carefully and then complete the student worksheet. Underlined words are defined on a separate vocabulary list. Most syntax and spelling are Montz’s; slight changes have been made for clarity. Selected hyphenations are spelled out in […].

May 16—June 1

Took things easy, drew equipment, time off to Torquay, took a few short marches to keep in shape (6 + 4 miles). A few days before June 1st we were briefed, shown maps + sand table of where we were going. Everything in good shape. I was executive officer, but will take 81mm [millimeter]. Wittenberger does not know mortar. Officers in Co. [company]: Buckles, Woodruff, Wittenberger, Levy, Buckalew, Olson, Exec. Montz, CO [Commanding Officer] Samson.

June 2

Left Camp at 1020 for Torquay, got on LCVP to go to ship (the S.S. Dickman). On ship life was OK.

June 4—Sun

Too busy to go to church—Making final preparation—Heard we sail today for landing tomorrow—weather very bad so thing’s called off. Spent most the night in lounge, drinking coffee + listening to radio. Heard the fall of Rome, in bed by 0200.

June 5—Mon

Heard we sail at 1300, Gen. Ike message read over the loud speaker after we sailed. Told D-Day June 6—H-Hour 0630. We anchor at 0200 June 6 + get in LCVP. Checked all equipment that was already in LVCP. Men in good shape + ready to go. Told that 10,500 planes would be in operation, 6000 bombers. Did not know anything except we land on Utah Beach Red + Green with 12,000 paratroopers landing H-4 inland. Messed around shooting bull + kidding each other. Channel pretty rough. Men will be fed at 2200, officers at 2400.

June 6—D-Day

2400—Eating a good meal, may be the last boat team. Sea very rough. Started loading one, went down to compartment with my men about 0230, went over side, down net + it was really tough.

Took off to rendezvous area, had a tough time finding it, made it o.k. Started circling, finally the other boats came in. Planes lit up the beaches, AA fire starting, flares dropping, beautiful sight but it scares the hell out of you. All hell broke loose from the beach, some boats hit by 88. We are near beach + 88 opened up on the boat on our right + almost hit us. Some boats hit land mines, lucky we landed because much more we would have sunk—water still rough. Jumped out in waist deep water, about 500 or 600 yds from seawall, the longest I have ever seen in my life. M.G., mortar, + artillery fire around us. Finally in shallow water + able to run, had to miss all types of obstacles in + out the water. Picked up six rounds of 81mm ammo on the way, it seemed as though we would never reach the seawall. Men being blown up and hit all around me, you could hear them scream, it was horrible. Finally hit seawall, stopped to get a blow and bearing, Gen. Roosevelt walking around telling everyone to clear the beach or they would get killed. Rockets hit the third section—injured: Lts. [lieutenants] Levy, Arps, Singer, Cole, Sgt. [sergeants] Hasting—Killed: Cpls. [corporals] Herr, Brandt, Wadja.

Time to move or they will kill us all. Gen. Roosevelt gave me lots of courage. Under small arms + artillery fire. Navy left us 1000 yds. too far left, the left outfit caught hell. Moved in very fast, every house + tree loaded with men, they fire at you from all directions, very hard to see them as they use smokeless powder. Will get on to them soon then they will catch hell.

June 10—Saturday

1400—Hit by sniper as taking a squad to Co. A right flank, 100 yds. from road west of Monteburg. We were catching hell but know we will hold them, had 400yds to get to objective. On west to aid station, hit in neck + right leg. Bandaged up + put in ambulance to be taken to beach, then sent to England. Spent night in field tent, caught in air raid.

June 11—Sunday

Put on LCM + sent to hosp. [hospital] ship, impossible to sail due to “E” boats in Channel.

June 12—Monday

Sailed for England, destination Naval Hospital at Southampton. Got in pretty late, was fed, a good bath, clean clothes, a bed with sheets. Doctors looked at us.

June 23—Friday

Up early. Back to town, date with Sharon—had a few drinks, decided to go bicycling. Watched sunset + planes going over to Germany. Malvern is very nice, never been bombed + set on hillside. Spent a very fine evening, she is off this weekend so will see her tomorrow. Took bike back to camp.

June 24—Saturday

Slept all morning, met Sharon at 1400, went to Worcester. Like her very much, the best for a long time. Date Sun. to go horseback riding. Back to camp by six.

June 25—Sunday

Sharon, Bill, Shirley, Joe + I went to a tea dance. Ate at hotel. Met Larry + Freddie (Americans) good to speak to them. The more I stay in England the less I like the English, their ways + manners.

June 28—Wednesday

Will be glad to get to France, these S.O.S. troops are getting the best of me—they are all trying to get to the States. They should send some to the front + let them get an idea of what’s going on. Saw a show.

June 30—Friday

Woke up at 0600 by the bugler, first one I heard for a long time. Nice sunny day so camp doesn’t look too bad, food very good, jaw + neck healed but scab still on leg. Went to Yeovil and saw a show, had a few beers, back early.

July 1—Saturday

Nothing to do in camps except eat + sleep, new replacements waiting to be sent out, men belonging to outfits waiting to be sent back.

July 2—Sunday

Sharon + I took a long walk in the rain. Reminded me very much of the States. These English are getting more + more on my nerves.

July 4—Tuesday

Small celebration on post, band played the usual 4th stuff + a little jazz. Expect to leave this place soon.

July 5—Wednesday

Taking things easy today, wrote home + to Sharon. We seem to be giving the Germans “Hell” from all sides, hope to be in the thick of things soon.

July 6—Thursday

May leave to-morrow, was told to hang around camp. Having a very good time here but still like to be with the outfit. These SOS troops should be sent to the front for a few days then they will have an idea what things are.

July 8—Saturday

Went to Salisbury for the trip, very nice place, saw a very old cathedral, messed around, back to Chard for supper. Had ice cream and fresh eggs to-day in Salisbury—first for a long time.

July 17—Monday

Ankle (left) giving me hell, swollen + can hardly walk—man in infantry with both legs bad. Ha! Ha!

July 19—Wednesday

Censored mail for 3 hrs.

July 24—Monday

I am on the alert to leave for France soon. I have charge of 250 men.

July 26—Wednesday

On train for Southampton, arr. 1100, sailed on the Louth at 1700, a limey tub built in 1906, made [was promoted to] troop commander + now have 500 men. Quiet trip.

July 27—Thursday

Anchored at Omaha Beach, walked about two miles to holding station, put in 233 Rep. Co. [replacement company] 69 Repl. Bn.[replacement battalion] 739. Jerry bombed the beaches all night, can hear big guns in the distance, going to front tomorrow.

July 28—Friday

Went to aid station to change bandage, sent to 7th Field Hospital to be sent back to England, leg not healed yet. Another night of bombing.

Vocabulary

Torquay—an English seaside resort town on the Southern coast of England

sand table—a three-dimensional map of a battle site, used to soldiers for an upcoming assault

81mm mortar—a short-barreled field cannon used by the US Army

1020—10:20 A.M. Army time runs on a 24 hour cycle: 1200=12:00pm, 1300=1:00pm, 2300=11:00pm, 2400=12:00am, 0100=1:00am

LCVP—Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel; the most-used landing craft during the Normandy invasion; it could carry 36 men or a jeep and 12 men from ship to shore

thing’s called off—D-Day was originally scheduled for June 5, but bad weather postponed it one day

fall of Rome—The US Army liberated Rome on June 4, 1944 after more than 5 months of fighting the Italians and Germans in Italy

Gen. Ike—General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force

D-Day—the military designation for the day of a major military assault; the D stands for “day”

H-Hour—the military designation for the time of a major military assault

Utah Beach Red and Green—two sections of the western-most beach of the Normandy invasion; United States forces landed at Utah and Omaha Beaches, the British landed at Gold and Sword Beaches, and the Canadians landed at Juno Beach

H-4—stated as “H minus four,” meaning 4 hours before H-Hour

Channel—the English Channel; the 100 miles of water separating the south coast of England from the Normandy coast of France

down net—LCVPs were lowered from larger ships into the water then fully-loaded soldiers climbed down cargo nets into the waiting craft

rendezvous—a designated gathering area

AA fire—anti-aircraft fire from the ground

88—the German 88mm gun, a long-range anti-air craft, anti-tank, anti-personnel gun most feared by the Allies

M.G. fire—machine gun fire

obstacles—the Germans placed a variety of steel and wood obstacles in the water and on the beaches to stop Allied landing craft, vehicles, and soldiers trying to come ashore. Many of these obstacles were topped with mines

Gen. Roosevelt—General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., son of President Theodore Roosevelt, was assistant division commander for the 4th Division and one of the highest-ranking soldiers on the beaches D-Day morning

smokeless powder—this type of explosive does not release a visible puff of smoke when a gun is fired

LCM—Landing Craft Mechanized, a British landing craft that could carry an 18-ton tank from ship to shore. Many landing craft were used to ferry injured soldiers back to hospital ships

“E” boats—fast German attack boats

S.O.S. troops—Service of Supply troops; these men were in charge of war supplies and loading and unloading material on the docks

censored mail—all mail sent from soldiers was read and censored for sensitive information by the military. Injured soldiers often assisted in this task.

limey—a slang term for a British sailor or ship; derived from the fact that citrus juice was once served aboard ships to ward off scurvy—a disease caused by lack of vitamin C

Jerry—an Allied slang term for German soldiers

Primary Source Gallery:

Discussion Questions

1. What was Montz’s life like in military camp? Give details and a more general analysis.

2. What details about D-Day can you discover from the June 6 entry? What information about the invasion is not included in Montz’s diary?

3. How was Montz injured four days after D-Day? Can you tell how bad these injuries were?

4. Can this diary teach us anything about slang used during WWII?

5. What were Montz’s opinions of England—positive and negative?

6. Are you able to describe Montz’s personality from these diary entries?

7. What can we learn about wartime conditions in England from this diary?

8. Is this diary only helpful in researching Sidney Montz or can it be used to research broader subjects?

Discussion Questions: Diaries as Primary Sources

1. How does the proximity of the writing about an event to the event itself affect the value of the source to a researcher?

2. As a primary source, what are the strengths and weaknesses of a personal diary?

3. What other primary sources could a researcher use to substantiate or further develop information from a diary?

4. How can a researcher distinguish between fact and opinion in a diary? How can opinion be a useful research tool?

5. Are there any ethical questions involved with using someone’s private diary for research?

A Postscript: July 29, 1944 to December 2, 1945

What happened to Sidney Montz after his return to England? With his leg finally healed, he was sent back into the fighting in Europe. He was awarded the Bronze Star medal. His medal citation reads, “…for heroic service in connection with military operations against an enemy of the United States in France, Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany, 6 June to 10 June 1944; 17 November 1944 to 24 January 1945; 12 February to 18 February 1945. Lieut. Montz rendered conspicuous service in his assignment as leader of a mortar platoon. He landed on D-Day in Normandy and capably and courageously led his men until he sustained a wound four days later and was evacuated. He returned to duty at the beginning of the bitter Hurtgen Forest operation and proved exceptionally adept in selecting feasible mortar positions in the densely wooded terrain.” In all, Montz saw combat at Normandy, Northern France, the Ardennes, the Rhineland, and in Western Germany. For service in those operations he had an oak leaf cluster added to his Bronze Star, two clusters added to the Purple Heart he was awarded on D+4, and he was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation and a European Theater Ribbon with five battle stars and bronze arrow head. On December 2, 1945, Montz was discharged from the army.

Other Classroom Uses of Montz's Diary

- By tracing Montz’s experiences on a map, his diary can be used as a D-Day geography lesson. His movements before, during, and after D-Day show the extent to which southern England was mobilized for the invasion and its aftermath. On detailed maps of England and Normandy have students label: Torquey, Utah Beach, Omaha Beach, Montebourg, Great Malvern, Yeovil, Southampton, Salisbury, and Chard.

- The personal thoughts of a diarist can make powerful and instructive statements in a visual project. Have students choose descriptive and thought-provoking passages from Montz’s diary to use as captions for various D-Day visuals they find during their research.

- There are many sources describing the Allied landings on D-Day. How does Montz’s diary description of June 6, 1944 compare to other written descriptions? Have students compare and contrast Montz’s story with a textbook version of the D-Day landings. Tell them to list the pros and cons of both versions of the history.

Download a printable pdf version of this lesson plan

TAKE ACTION:

EDUCATION PROJECTS:

Student Travel – WWII Educational Tours

High school and college students, learn the leadership principles that helped win WWII on a trip to France or during a weeklong residential program in New Orleans. College credit is available, and space is limited.

See You Next Year! HS Yearbooks from WWII

Collected from across the United States, the words and pictures of these yearbooks present a new opportunity to experience the many challenges, setbacks and triumphs of the war through the eyes of America’s youth.

The Victory Gardens of WWII

Visit the Classroom Victory Garden Project website to learn about food production during WWII, find lesson plans and activities for elementary students, get tips for starting your own garden and try out simple Victory Garden recipes!

The Science and Technology of WWII

Visit our new interactive website to learn about wartime technical and scientific advances that forever changed our world. Incorporates STEM principles to use in the classroom.

Kids Corner: Fun and Games!

Make your own propaganda posters, test your memory, solve puzzles and more! Learn about World War II and have fun at the same time.