FOCUS ON: D-DAY SKY SOLDIERS:

When US assault troops waded through the cold dirty water of the English Channel in the early morning hours of 6 June 1944, their airborne brothers-in-arms had been wreaking havoc on the German rear echelon for some five hours. For most paratroopers, this moment was the culmination of two years of the most rigorous and unforgiving training the Army had to offer. Paratroopers were an all volunteer force, bred for the concept of vertical envelopment—the ability to strike the enemy’s rear area with little or no warning.

The tactic of vertical envelopment had been a dream of military commanders for centuries. The Germans, however, made it a reality with the airborne invasion and capture of the Greek island of Crete in 1941. This amazing feat of arms made the US Army take seriously what had been up to that point a novel theoretical idea. US airborne forces expanded from a small test platoon in 1940 to four combat-ready divisions by D-Day.

As it was the mission of the men of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions to pave the way for the sea-borne invasion, so it was the mission of the men of the 8th and 9th Air Forces to clear the skies of German opposition. The first act of the D-Day invasion had been playing out for the six months previous to the invasion. Bomber crews took to the air everyday to strike vital German targets in France and Germany. Fighters roved the French countryside strafing any German target with wheels, hoofs, or wings.

The result of the combined efforts of the airmen and airborne soldiers of D-Day resulted in minimal aerial resistance by the Luftwaffe, and the denial of reinforcements to the German beach defender, all of which contributed immensely to the overall success of the invasion of France: Operation Overlord.

The Paratroopers

Due to the inherently chaotic nature of any airborne operation, soldiers of the 82nd and 101st were trained for situations in which conventional soldiers would seldom find themselves. In the opening hours of D-Day, many troopers ended up alone and quite often surrounded by the enemy. For this reason, a premium was placed on self-reliance; troopers were highly skilled in land navigation and the use of explosives and enemy weapons. Every trooper, regardless of rank, was armed with the knowledge of their unit’s objective, ensuring that even a solitary trooper was capable of completing his unit’s mission, a concept unheard of in the German army. But for the paratroopers, self-sufficiency came at a price. The average load carried into combat often outweighed the man carrying it. Troopers had great difficulty climbing aboard their aircraft and required assistance. The heavy load also drowned many paratroopers who landed in the fields that the Germans had flooded in anticipation of an airborne invasion. However, the mass scattering of paratroopers that occurred on D-Day was due to the evasive action taken by the C-47s to avoid anti aircraft fire, and ultimately served to convince the Germans that they were under attack by a much larger force than they actually were.

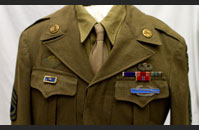

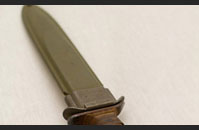

Paratrooper Artifact Images from The National World War II Museum Collection:

The 82nd Airborne

Glider Troops

During World War II, aircraft large enough to drop jeeps and artillery pieces were not available. The only solution to providing airborne forces with artillery support lay in towed gliders. Gliders were unpowered aircraft which were towed by C-47s into landing zones inside hostile territory. When the gliders were close to the landing zones, the tow ropes were cut and the gliders made a crash landing, often resulting in injuries and death to the passengers.

However, upon a successful landing the gliders placed tightly grouped, cohesive units behind enemy lines. Whereas parachutes put one dangerous soldier in the enemy’s rear area, the glider put thirty.

Glider Troop Artifact Images from The National World War II Museum Collection:

The Pathfinders

For paratroopers entering enemy territory, few sights were as welcome as a drop zone illuminated by the signal lamps laid by pathfinders, who had the dangerous job of jumping behind enemy lines before the main parachute assault. Always first on the ground, these specially-trained paratroopers carried out a mission to keep hundreds of planeloads of paratroopers from becoming scattered during the drop, despite being surrounded by the enemy and outnumbered by extraordinary odds. The pathfinders used lights, radio, and radar to guide incoming aircraft to the correct drop zones and mark landing zones for their fellow airborne soldiers. After all of the paratroopers had landed, the pathfinders fought alongside the rest of the airborne forces.

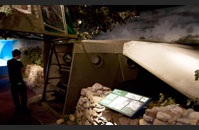

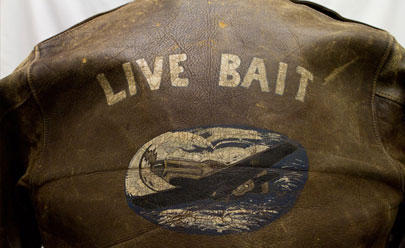

Pathfinders, like the rest of the paratroopers, jumped from C-47s. A typical C-47 aircrew consisted of five men: pilot, co-pilot, navigator, radio operator, and crew chief/flight mechanic. The elite crews of Pathfinder aircraft such as The National World War II Museum’s own, known as #096 or chalk #17, were handpicked from the ranks of transport squadrons. They were experienced, and included many combat veterans from earlier airborne operations in North Africa and Sicily. Their mission required bravery and precision, and was extremely dangerous. Pathfinder aircraft were the first transports over enemy territory, dropping pathfinder paratroopers from the Army’s airborne divisions in advance of the main invasion force.

Artifact Images from The National World War II Museum Collection:

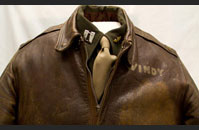

The Fighters

P-51 fighter pilots Jack Bradley and Clayton Kelly Gross had been taking the fight to the enemy since the arrival of their unit, the 354th Fighter Group, in England in the fall of 1943. In the months leading up to D-Day, Bradley and Gross accounted for the destruction of eighteen German aircraft in the air, and numerous trucks, tanks, trains and other vehicles on the ground which would have otherwise been available to oppose the Allied landing. On the night of 5 June, Gross and Bradley escorted C-47s and gliders carrying the airborne forces spearheading the invasion.

Aerial Enemy: Herbert Hüppertz and the Luftwaffe

Hauptmann Herbert Hüppertz of JGII was part of the meager Luftwaffe presence over the invasion area. The 25-year-old 78-victory ace flew several sorties on D-Day and in the days immediately following. The sheer numbers of Allied fighters then roaming the skies of Normandy made the Luftwaffe’s mission nearly suicidal, even for highly experienced German fighter pilots such as Hüppertz. On 8 June 1944, Hüppertz was shot down and killed by P-47 fighters over Caen.

Bradley:

Gross: