FOCUS ON: WOMEN AT WAR:

When the United States entered World War II, the US government called on women to contribute. With hundreds of thousands of American men entering the military and going overseas, more women would work outside of the home than ever. Many would be promoted to positions never before attained by women, all the while managing their households alone for the first time. Though professional and personal growth opportunities were many, women’s main charge was to support the war and the men fighting it. The War Department stressed to women that the harder they worked, the quicker their brothers, husbands and sons would return home.

There were just over a thousand women in the military before World War II, serving either as Army or Navy nurses stationed in the United States. When war broke out, women wanted to contribute militarily and fought for the opportunity to join. The Army, Navy, Coast Guard and Marine Corps came to rely heavily on women in crucial stateside jobs, as well as work overseas. By the end of the war, there were more than 288,000 women in the US Armed Forces.

Below are some of the important roles women filled in wartime. The National WWII Museum is actively seeking additional artifacts and personal stories for our collection that speak to the female experience during WWII. Find out more about donating artifacts to the Museum. You can find additional artifacts commemorating women's service in World War II under Featured Artifacts

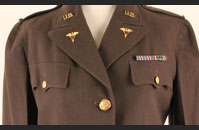

Estelle Gage Coleman, Army Nurse Corps:

The United States Army had fewer than 1,000 nurses in its Nurse Corps when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. By the end of World War II, more than 50,000 women had served their country in this capacity. Army nurses served under enemy fire in field and evacuation hospitals, on hospital trains, hospital ships and in general hospitals overseas as well as in the United States. Frequently serving near the front lines, they suffered casualties. The first Army nurse to die while on duty was killed in a plane crash in 1943. Two hundred and one Army nurses died during the war, sixteen as a result of enemy action.

Estelle Gage volunteered for service in early 1943, and was assigned to the United States Army Hospital Ship Shamrock in July. The Shamrock evacuated patients from the Mediterranean to the United States, collecting patients from Oran, Algiers, Bizerte, Palermo, Naples, Corsica and St. Tropez, and shuttling them back to Charleston, South Carolina. Estelle made three trips as a member of the crew and completed her Army nursing duty at Stark General Hospital in Charleston.

Violet Kochendoerfer, The American Red Cross:

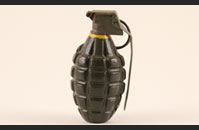

Vi Kochendoerfer served with the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, the predecessor to Women's Army Corps, before joining the American Red Cross. She served as director of on-base service clubs for the 315th Troop Carrier Group in England during D-Day and its planning phase. Since the operation was postponed on 5 June due to poor weather, thousands of soldiers were restlessly waiting for orders when Vi caught a GI stealing donuts from her club's kitchen. When he explained that he was simply trying to placate the antsy soldiers, she let him keep the donuts. In exchange, he tore off his sergeant stripes saying, "Probably won't need this" and gave it to Vi along with a hand grenade, which they emptied of its powder so that she could keep it as a (nonlethal) souvenir.

Though directing a club may not sound like the toughest of jobs, it was certainly one of the most human and meaningful. Vi recalled, "after one [soldier] came in to pour out the fact that his wife was seeing another man, selling their house, etc. and there wasn't anything he could do about it — I came to know that under every one of those fatigue hats was a separate human being with fears and joys and all."

Oral History: Barbara Pathe, Red Cross "Clubmobiler"

From the collection of oral histories at The National WWII Museum, hear Barbara Pathe recount some memorable moments during her service as a Red Cross staff member serving coffee and donuts to troops in World War II.

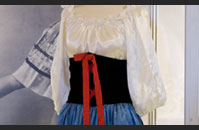

Betty Jacobs Schwartzberg, Entertainment:

As a young girl from New Orleans, Betty Jacobs attended Lelia Haller School of Dance on Canal Street. When the United States entered World War II, she was in the eighth grade at Isidore Newman School. Haller's dance troupe soon began performing all around Louisiana and Mississippi for servicemen. Betty recalled:

At least three or four times a week we would meet the big Army pickup truck and they would take us to different bases: Camp Beauregard, the Naval Air Station, every camp, Camp Leroy Johnson, the hospital. I vividly remember going to the Marine Hospital — just sad. It was very traumatic for a thirteen-year-old to see such maimed young men…. We just went and we visited with them. And we would take them treats; my mother would make cookies or something, even some smelling aftershave lotion or something like that that the hospital director would tell us would be a little treat for them.

At Camp Plauché, Betty's troupe performed a show called "Yankee Doodle Dandy" with some of the servicemen included in the cast. The entire Jacobs family helped in the patriotic cause — visiting hospitals, teaching classes at serviceman's centers, dancing at camps, bringing servicemen home for dinner. Volunteering as a teenager had a deep effect on Betty. She later said about World War II, "I also realized that I lived in a wonderful, wonderful country and it made me just so proud to be an American and to be in this country."

Sylvia Cohen Corwin, Home Front:

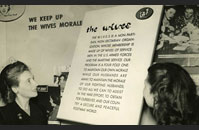

While Rosie the Riveter may be the most recognizable Home Front poster girl, Sylvia Cohen and her women’s group known as W.I.V.E.S. (Women Insure Victory, Equality, Security) contributed their part too. The group had its own creation myth, beginning at Camp Stewart, Georgia:

Five soldiers telephoned their wives, asking them to board a Georgia-bound train. Five wives hurriedly packed. Each knew her husband was to be shipped out. These women met, for the first time, at Camp Stewart. The men left for overseas. The wives were left behind. Out of a common need, they formed the first of several W.I.V.E.S. chapters in New York City.

The group had four main goals: to maintain their own morale while their husbands were away; to maintain the morale of their fighting husbands; to do everything possible to assist in the war effort; and finally, to obtain for themselves and for our country a secure and peaceful postwar world. Their motto was "We had war in our father's time. We have war in our husband's time. We want peace in our children's time."

Each chapter was named after a famous woman in American history. Sylvia, for example, belonged to the Eleanor Roosevelt chapter in Manhattan. The images below include a few of the pages from a portfolio which Sylvia designed herself. Beginning in May 1942, Sylvia worked as a civilian chartist and draftsman for the War Department in Washington D. C., which made designing and drawing the portfolio an easy task for her. Her chapter shared their information at an Arts and Sciences Expo in Manhattan in 1944. Included in the booklet was information about the "average wife," according to surveys they had conducted which showed that most were 26 years old with brown hair and brown eyes, between 115 and 125 pounds, had been married between two and three years, and 84% had husbands serving overseas. As for employment, 21% were mothers, 41% were defense workers, 14% were not employed, 11% were professional workers and the remaining 13% were categorized "miscellaneous."

W.I.V.E.S. visited veterans' hospitals every weekend, toting fresh-baked cakes and good cheer, playing ping-pong and cards with the patients. Local bakeries and stores would donate treats and nice clothes to bring with them to the hospitals. They took turns selling war bonds, often giving speeches at movie theaters before the film began. Perhaps the hardest but most important role played by the members was empathizing with those whose husbands were killed in combat. Sylvia recalled, "We grieved with and supported the widows in our group. Seven men were either killed or missing in action from our chapter alone." On a lighter note, the wives also took pin-up style photographs of themselves to send to their husbands along with care packages, a sure way to keep up morale!

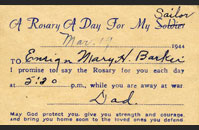

Mary Barkei Marler, Navy Nurse Corps:

Registered Nurse Mary Barkei served with the Navy Nurse Corps during World War II. She was initially stationed in the United States, but in 1944 she received orders to go overseas with Naval Mobile Hospital No. 10. While sailing to her new post, she wrote to her mother, "Never as long as I live will I forget or regret this trip. Now after nearly a year and a half of so called Navy life, I may have a chance to do what I came in for." Her mobile hospital was located on Banika, part of the Solomon Islands.

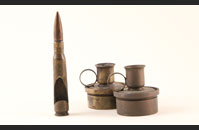

Despite its mobility, the hospital included eighteen surgical wards, twelve medical wards and a clinical laboratory. Naval Mobile Hospital No. 10 could treat 2,000 patients at a time, and only 15 of the 10,000 patients admitted between March 1944 and June 1945 died while at the hospital. Despite the long hours and hard work, Mary found time to purchase souvenirs to send home. She sent the candlesticks and letter opener, made on New Caledonia, home to her family. Mary returned to the United States in October 1945.

Mary Mills Weinmann, SPAR:

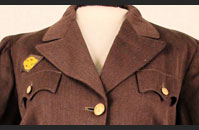

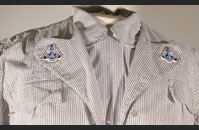

The United States Coast Guard Women's Reserve was statistically the smallest women's reserve unit in the war. The group was called the SPARs, created from the Coast Guard's motto, "Semper Paratus,Always Ready." Congress created the reserve on 23 November 1942. Between then and the end of the war, more than 10,000 women served in the SPARs. They were issued WAVE uniforms, but SPARs were differentiated by the distinctive United States Coast Guard insignia on their uniforms.

The dress uniform below was issued to Mary Mills Weinmann, who served in the United States Coast Guard Women's Reserve between 16 September 1943 and 30 September 1945. She was assigned to the Coast Guard Port Authority in New Orleans, Louisiana. As part of the Port Volunteer Security Force, Mary was responsible for tracking ships and airplanes in the New Orleans area.

Charlotte Kerr Boissonneau, US Marine Corps Women's Reserve:

Ray and Charlotte Boissonneau were the first married couple during the war to enlist for military service from Portland, Maine. Ray served in Patton's Third Army, while Charlotte enlisted in the Marine Corps Women's Reserve. The Marine Corps was the last of the Armed Forces branches to recruit women during World War II, doing so in 1943.

Charlotte was stationed at the Navy Annex in Arlington, Virginia, from September 1943 until November 1945, which delighted her since she had family in the D.C. area. At first she had trouble getting to work on time because she had to ride three separate buses very early in the morning, and at least one of them got lost every day. However, she was soon offered a daily ride to work by a colonel and two brigadier generals in her office so that they could meet the occupancy requirement to have the government pay for gas. One of Charlotte's last duties before being discharged in 1945 was to march in Admiral Chester Nimitz's homecoming parade, which felt to her "like they were all dancing."

Adah Mae Briscoe, WAC:

Adah Mae Briscoe joined the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1942, before it was fully incorporated into the Army as the Women's Army Corps (WAC) in 1943. Her father "had a fit," in her words, and she was sure he wouldn't let her go through with it. But she did, first training at Camp Oglethorpe, Georgia, and then at the Army Administration School in Nacogdoches, Texas.

Adah eventually ended up in Virginia with the Classified Reproduction Section of the Adjutant General's Office (AGO), where one of her duties was reproducing Restricted, Confidential, Secret and Top Secret material — including information regarding the D-Day landings and the dropping of the atomic bombs. She worked in the basement of the Pentagon, known as "the secret room," always under guard.

After the war, Adah and her coworkers were complimented by their superiors, hinting at the changing role of women due to their wartime contributions:

There were those who expressed doubt that women could cope with the arduous and complicated duties assigned to you. Your zeal, efficiency and loyalty made it possible for you to surmount these difficulties. This is attested to by commendations from the Secretary of War, Chief of Staff, War Department General Staff, Commanding General (Army Service Forces), the Adjutant General, and chiefs of staff divisions and technical services.

A separate letter of appreciation discussed the WACs' "devotion to duty, willingness to execute exacting assignments, and achievement of difficult deadlines…. Your contribution to the war effort has been a great one."

Donna Kriner, WAVES:

Donna Kriner enlisted in the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) in July 1943, at the age of 21. She opted for the WAVES, the women's component of the US Navy at the time, over the other branches because WAVES were the only group that was sent to Hawaii for service at the time. Her first stop after enlistment was in New York City, where she was fitted for her uniform and her group was inspected by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

What Donna remembered most from boot camp was learning to march properly. It came particularly easily to her, as her parents had enrolled her in etiquette and posture lessons as a young girl. She graduated from Naval Training School conducted at Indiana University, Bloomington in November 1943, earning the rank Storekeeper 2nd Class. Upon graduation she had all of her classmates sign a stuffed animal, their class mascot. Donna was discharged in February 1946.

Educational Materials:

Learn more about Women in World War II by reading and downloading the Women in WWII Fact Sheet.

Learn More with Items from the Museum Store:

Proceeds from Museum Store purchases fund the continuing educational mission of the Museum in New Orleans.

The Girls of Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II

by Denise Kiernan

Drawing on the voices of the women who lived it — women who are now in their eighties and nineties — The Girls of Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II rescues a remarkable, forgotten chapter of American history from obscurity. Denise Kiernan captures the spirit of the times through these women: their pluck, their desire to contribute, and their enduring courage.

Price: $27.00